She has spent 50 years beguiling and outraging audiences in equal measure. The artist provocateur talks fearlessness, feminism and what shes done for Kim Kardashian

Dont bring your underaged children or grandchildren. Dont bring your grandmother or other relatives. Dont bring your out-of-town guests. The current exhibit is awful. I dont know what it is, but it isnt art.

A new book about Carolee Schneemann begins with this warning from a visitor to one of her exhibitions. This review may seem harsh or hysterical, but its also fitting: at 76 years old, the artist still divides opinion. For the last 50 years, she has made art that tackles terrorism, war, sex, sensuality and love everything from the joyful to the more violent and ferocious aspects of American culture, with the outrage always coming from a very American sense of righteousness. The book chronicles it all. It is called Unforgivable.

Schneemanns art has always been raw and personal and often reviled. I ask if she sees herself as fearless. No, I think Im stubborn, she says. In the beginning, I had no precedent for being valued. Everything that came from a womans experience was considered trivial. I wasnt sure if my work would shift that paradigm or not, but I had to try.

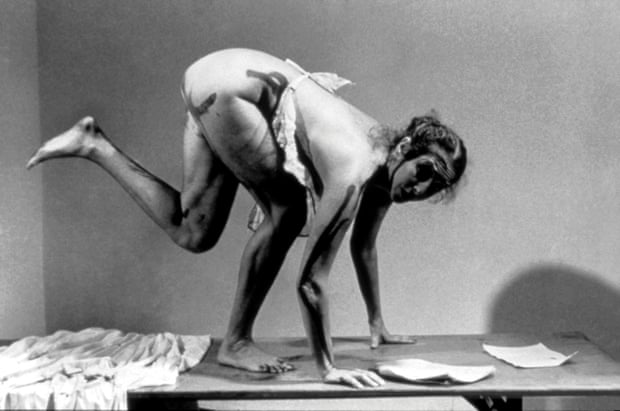

Schneemann didnt just shift the paradigm she exploded it. Works like Eye Body, from 1963 (in which the naked artist appeared as a warlike Gaia, covered in feathers and fur) met the male gaze unblinking although critics were more alarmed by the sight of her clitoris than by the snakes decorating her torso.

She had a dancers poise, which she used for perversion in pieces such as the film Up to and Including Her Limits, in which she painted while nude and swinging in a harness. Keen to discard feminist cliches, she wanted audiences to see her as ecstatic rather than angry. My work doesnt have any kind of furious narrative, she explains. It emphasises energy.

Schneemann has always resisted being called a performance artist. Instead, she considers herself to be a painter always a painter, using her body to reject performative womanhood with its desire for pristine, immaculate sex.

Performance has these connections with cultural pleasure, for a male audience, she says. Its the tradition of the dancer, the striptease, the beautiful actress. Male performance, by contrast, is usually highly masculinised. Its challenging the body in a very physical way. Its climbing a mountain instead of laying on a glacier in your underwear. Men who practised early happenings such as Claes Oldenburg and Jim Dine were given the label mixed media, whereas women like her were pigeonholed. All those men were given credit for sculpture, for installation, she says. Womens use of other materials tends to be denied.

Her most celebrated work, Meat Joy, was first performed at the Festival of Free Expression in Paris in 1964. Its shopping list of ingredients raw fish, chickens, sausages, wet paint, plastic, rope and shredded scrap paper suggested an orgy of cooking or craft. The work, which culminated in a group of participants writhing in paint and raw meat, was comic, unsettling and sexy all at once driving an audience member so wild that he tried to strangle Schneemann halfway through. Public reactions, even now, are rarely neutral. This is a revolting, excessive, vulgar thing, reads a comment beneath a YouTube clip of a performance, and I hate it, I hate it, I hate it!

Schneemann was playing with the idea of womens work at a time when it was confined to the bedroom or the kitchen. Fuses (1965), a sensual and abstract film of the artist and her partner having sex, took her interest in female passion even further. Her visible pleasure dared to suggest that what women did in the bedroom did not, in fact, feel much like work at all. David McCullough, the Pulitzer prize-winning author, saw the film the year of its release without knowing who had produced it, but he reasoned that its creator must be a woman: The cultural history of male America has passed down too much shit for a man to have made Fuses, he wrote, which views lovemaking subjectively, from within. Director Jonas Mekas agreed, calling it his film of the year: It is so gorgeous so dangerous.

Fuses caused rapture and outrage in equal measure, recalls Schneemann. There were men who said they resented the eroticism. There were women who said it displaced their privacy and played into male fantasies. But it was also liberating for people, and gave them a basic sense of how pleasurable heterosexual intercourse could be.

The reactions that hurt most, she says, were other feminists who, in the 70s, rejected my work as playing into male traditions rather than countering them. The whole concept of pleasure and sexuality was being contested. That was very painful for me.

As feminism evolved, her work became not only accepted, but seminal. In the context of new feminism, with its pro-sex attitudes, Schneemanns early work began to seem like a prescient glimpse of the modern woman: I mean, coming out of the 1960s, you couldnt even say vagina or orgasm! Today, culture is less neurotic about sex, but the underlying phobias keep finding their way into commercialisation, and into these glamourised depictions in the media.

Later works such as Terminal Velocity, which magnified images of the victims of 9/11 jumping from the twin towers, as tribute, faced a different kind of opposition. I have a long history of working with war: with the mutilations in the Vietnam war, which was central to the 60s, the destruction of Palestinian culture in the early 80s and the bombardment of Lebanon. But with Terminal Velocity, there was this idea that Americans were never going to be seen as the victims. Having revolutionised the depiction of sex, she is equally unafraid of examining death and in both, she pits emotion against machismo.

Schneemanns focus on sexuality has had an enormous influence on how we view the female body. But her other great interest is movement: movement while painting in her harness, the womens movement, the movement of bodies in Meat Joy, alone and together.

Mostly, however, its about forward movement: Schneemanns focus is always on advancing. Going back to the issues of the 70s is really regressive. Its good that weve been through that kind of analysis, and its over, she says. Now, women artists are having a renewed history, she adds, delighted at the development, and a renewed sense of authority.

Still, there will always be something challenging about womanhood, sex appeal and radicalism. Several pieces published about Kim Kardashians book Selfish, which is comprised of selfies of the reality star, billed Schneemann as her highbrow ancestor. It wasnt intended as an entirely flattering connection. But Schneeman is candid about her role in the genesis of the private selfie or the cameraphone nude. My early work with the body was like a bridge, she says, built so that other women could pass over it. I gave them permission.

- Unforgivable is out now, published by Black Dog Publishing.

Read more: www.theguardian.com

![[Video] How to get rid of bed bugs in Toronto](https://www.thehowtozone.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/maxresdefault-2-100x70.jpg)