Abra Annes doesn’t get uncomfortable. The emotion evoked by first dates, small talk, and personal questions doesn’t plague a woman who’s made a career asking strangers for huge sums of money while wearing head-to-toe floral print.

“A big piece of my job is embracing the awkward silences of fundraising,” the 35-year-old Californian says. “You have to ask, and then just shut your mouth and enjoy the silence. The silence settles and it can be heavy—and sometimes people get so uncomfortable that they’ll give more to fill the void. I enjoy the silence.”

As a professional fundraiser, Annes works primarily with non-profits to rake in as much cash as possible from wealthy donors. Her consulting fee starts at $4,000 and tops out at $10,000—plus a bonus if she brings in more than the preset goal.

Annes is a benefits auctioneer, among the fastest growing specialties in the industry, according to the National Auctioneers Association. Benefits auctioneers specialize in nonprofit fundraising—they aren’t the buttoned-up, gavel wielding art house auctioneer that may come to mind, and certainly not the hundred-miles-a-minute version that presides over a cattle pen.

Millions of dollars are forked over annually in the name of some greater good as Americans bask in the self-affirming glow of a charitable event. Charities host them for two primary purposes: soliciting donations, and meeting new people from whom they can solicit more donations.

In exchange, eventgoers are treated to an open bar, dinner, entertainment, and cameras ready to plaster their faces on the society page. The fundraising element can come in many forms: a silent auction, a traditional auction in which items and elaborate trips are sold off, or so-called fund-a-needs—Annes’ specialty.

The charity business

Typically, Annes is hired six months before an event. She gets involved in everything from social media strategy to the style of invitations, as the tiniest detail can influence how guests donate. “I don’t believe you can have a successful fundraiser unless I know how the fundraiser is supposed to work,” she says. “Your auctioneer up on stage is basically the emissary of the organization.”

Before she agrees to a job, she researches the group to ensure her values align with it. Her passions include the environment, social services, education, Jewish services, and children’s aid. She declines requests to discuss politics on stage.

If she signs on, Annes and the charity’s staff conduct a series of calls to plan out the strategy, invitation list, event flow, honorees, and social media strategy. Perhaps most importantly, she focuses on seating so she knows where to look for the most money.

“Where are your heavy hitters?” is the key question she asks.

At a fund-a-need event, the audience is asked to make a donation in exchange for nothing but gratitude, albeit in a public forum. The auctioneer begins by asking if anyone is willing to donate an enormous sum of money—in some cases $100,000 or more—then works their way down to more accessible donation requests.

“At any auction, no matter what the organization, you only have, total, maybe eight to 15 bidders. They’re going to bid on everything. The rest of the audience will sit there and watch,” Annes says. “But in the fund-a-need, everyone can participate. Everyone has the capacity to give. Everyone can afford $50. That’s where most organizations bring in the big money.”

Annes contends she can typically increase donations by 50 to 100 percent from a previous year’s event during a fund-a-need. “You should really only hire me if you’re ready to take your auction to the next level,” she says. “If you want to move from $500,000 to $1 million, or $1 million to $2 million. But I don’t do your neighborhood school auction.”

Cruise line warm-up act

Annes has a signature opening move. “I go out into the audience and I ask for something, something that’s auctioned off somebody. I've taken a dollar out of a tech founder’s wallet, or I’ll take a tie off of the Ambassador to India, or M.C. Hammer’s glasses or Will.I.Am’s headphones,” she explains, checking off some boldface names. “They go anywhere from $500 to $20,000. A one dollar bill and used headphones have no value. [But] that gets the crowd warmed up and ready to go.”

It’s all an illusion, of course. The tech founder, Ben Silbermann of Pinterest, was approached in advance to ask if he would be comfortable having a dollar with his signature auctioned off, she says. Annes even handed him the buck to use. Will.I.Am (real name: William Adams) doesn’t randomly wear headphones to a charity event—Annes says she asked the music mogul to don them so she’d have something to take off of him and auction. This behind-the-scenes orchestration is a take away from her former, less glamorous career as a cruise ship “entertainer,” which meant everything from warming up a crowd to organizing hairy chest contests.

While studying at Northwestern University, Annes got a gig as a dancer for an entertainment company that hosted Bar Mitzvahs and birthdays. She worked her way up to emcee, and during her summers spent time interning for a communications firm, which offered her a job upon graduation. “My senior summer, I realized I hadn’t had a lot of fun in college,” she recalled. “I had been on a cruise and had seen all these cruise entertainer people using microphones. I went on Monster.com, I searched cruise. I got a call the next day.” Annes asked for a delayed start date at the firm, flew to Florida and boarded a Carnival cruise liner.

After a month, Annes realized she wasn’t going back. Instead, she worked about four hours a day setting up entertainment for cruise ship guests, much of which had to be organized ahead of the event. “We would go out on the pool deck and do ‘spontaneous’ games,” she says. One of the more frequent forms of entertainment was a hairy chest contest. “They would ask all the men with hairy chests to come down. But we would make sure the hairiest men were down already.”

In her off hours, Annes would bum around the ship, sunbathe, and occasionally sit in on art auctions. The auctioneer sometimes asked her to clerk the event. After seeing her work the mic during a pool deck event, he asked Annes to warm up the auctions. She stayed on the boat for almost three years, learning to work a crowd.

By the time she left the cruise ship, she was in her mid 20s, jobless, and carless. “A lot of my friends had gone the consulting route, Bain, McKinsey. And I could not get a job.” On a whim, she applied to the fundraising division of the Jewish Federation of Minneapolis. “I told them because I was on a cruise ship, I had a lot of experience selling things to people. If I can ask people to be in a hairy chest contest, I can certainly ask people to donate money.”

Language and tactics

Mentored by a fundraising expert who taught her the language and tactics of the industry, Annes stayed with the nonprofit for several years, jumping to the San Francisco office. “I went to a charity auction myself and there was a terrible, terrible auctioneer,” she recalled. “I said, ‘Oh my god, this is everything I know how to do. I know how to entertain ask for money.’”

At another event, Annes ran into a more skilled auctioneer and took down his phone number. She repeatedly contacted him—and three other auctioneers—until she got a job. After some time working for someone else, she launched Generosity Auctions.

Today, Annes says she gets more requests than she can handle, doing as many as 50 events a year. She practices her fundraising skills constantly, recites speeches into a hairbrush while driving, talks to every person she encounters, and records each event to review later. But part of her skill as an auctioneer is a sort of sixth sense.

Annes has developed a formula for the fund-a-need: first she does an introduction and brings the room to a dead quiet. Then either a heart-wrenching or heart-warming story about the charity’s work is told, either by a speaker or through a video.

“People have to be focused. Then comes the transition from the speaker or video to the fund-a-need,” she says. “That transition has to be spot on. Perfection. I get hired most of the time for those three or four sentences. Then I go get the money.”

Fund-a-needs typically begin with a lofty donation in the tens of thousands. The big donor is committed in advance (part of Annes’ set-up) and usually gives at least $25,000, she says.

Sometimes, though, she will start higher than the pre-committed amount, depending on how the event feels to her. “That’s something I know in my bones,” she says. “It also depends how amazing the speaker was before me.”

Annes is mindful of her word choice. “You have to be willing to ask in a way you would want to be asked,” she says. “You have to sound very fun, very kind, very light. A lot of ‘us’ and ‘we’ language, instead of ‘you.’ During the fund-a-need, Annes uses inspiring language: she requests “a generous gift” or a “beautiful donation.” Sometimes she asks the crowd to make “an investment in the organization.”

In addition to reviewing footage of her events and rehearsing speeches, she practices memorizing names with mnemonic devices, so when she transitions from the event’s cocktail hour to the seated auction or fund-a-need, she can refer to people by name.

Floral, metallic, and baby pink

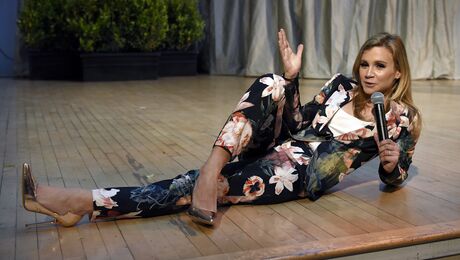

As a woman in a male-dominated industry, Annes is mindful of her appearance. “I study the shit out of all the other auctioneers in the industry. I know what they all wear. I have a spreadsheet,” she says. “Most of the women wear dresses and men wear tuxedos. What could I wear that will set me apart?”

Floral, metallic, and baby pink. Annes wears eye-popping suits, always completing the outfit with a metallic shoe—gold, silver, or even a blingy copper. “If you’re going to be the person who asks for money, you need to really own who you are and be able to be seen. Like, ‘yep, she’s the auctioneer!’” Her choice of attire is so popular that clients often make requests on which suit she should wear. She has a spreadsheet for this too, making sure the same crowd doesn’t see the same outfit twice.

Annes says she’s not just an auctioneer, but a participant in charitable giving as well. She sits on nonprofit boards and donates in the five figures annually. Startups have approached her to help with funding rounds, she says, but she’s not interested—though she says she’d love to get into political fundraising.

“I always work with people I believe in,” Annes says. “I don’t identify as an auctioneer—I feel more like a philanthropist. This is money we’re raising together. I’m helping other people raise their hand.”

Read more: www.bloomberg.com

![[Video] How to get rid of bed bugs in Toronto](https://www.thehowtozone.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/maxresdefault-2-100x70.jpg)