“A person’s name is to him or her the sweetest and most important sound in any language.” Though Dale Carnegie was talking about nurturing relationships, a lot of startups these days are incorporating his observation into branding strategy.

They are naming themselves after people.

Over the past few years, a crowd of new companies has emerged across tech, finance and health—all sporting a first-name brand. “Oscar,” “Alfred,” “Lola” —they have the look and feel of a friend, a colleague, maybe even your cat. And that’s the point: Make a connection with consumers that even Carnegie would appreciate.

“A short first name changes everything—as it’s unexpected, less concerned with sounding corporate and serious and is inherently more human,” said Steve Manning, the founder of a Sausalito, California-based naming agency that, of course, goes by one name: Igor.

The strategy seems to be working. Research shows that the more simple and human-sounding the name, the greater the company’s success. Brands with short, easy to pronounce names were viewed more positively by investors, a 2012 study published in the Journal of Financial Economics found. By reducing name length by just one word, companies can see a boost of 2.53 percent to their book-to-market ratio—a formula used to find the market value of a company—or $3.75 million for a medium-size firm, according to the study.

Likewise, a 2006 analysis by Adam Alter and Daniel Oppenheimer, professors of marketing and psychology, respectively, found that stocks with names and tickers easy to pronounce will outperform counterparts with more complicated names. The simplicity of naming tends to make it more likely people will invest in a company, they said.

The name game isn’t so much about the products or services being sold. It’s a subconscious approach to branding that borders on anthropomorphizing a company.

“If you don’t want to become commoditized, you need to have something special,” said Neil Parikh, co-founder and chief operating officer of mattress startup Casper. “Everything has a brand, from vitamins to your doctor’s office to mattresses, but the ones that have a sense of depth—where you can understand who that person might be like—those are the ones you want to interact with, because you can see what it’s like. It’s three-dimensional.”

The strategy has become an imperative to cut through the cacophony of online brands vying for attention. Gone are the times when a great product or service was enough. Consumers want an emotional connection, something that will cause them to develop brand loyalty—and it starts with the name.

As with any fresh trend, going the first-name route isn’t risk free, according to Jake Hancock, a partner of brand strategy at creative consultancy Lippincott. “Choosing names that signal a human experience really raises the stakes for a brand to deliver it throughout the whole experience,” Hancock, who specializes in brand naming, said. “If you name your company a person’s name, the customer is going to expect every interaction to feel like they’re dealing with a person.”

Here’s what a handful of companies said about the origin of their names—and whether or not consumers have actually taken to them.

Marcus

For Marcus, the personal lending startup founded in 2016 by Goldman Sachs Group Inc., the biggest question before launch was how big a connection the brand would have, at least publicly, to its parent company.

“When you called it ‘Goldman Sachs,’ consumers said ‘Well, I’ve heard of Goldman Sachs, but that's not for me—that’s for wealthy people and institutions,’” said Dustin Cohn, head of brand management and communications at Marcus. He’s also led the unit’s “brand architecture,” which included choosing a name.

After whittling down 2,000 contenders to just 10, “Marcus” was added at the last minute, he said: the only human name on the list.

“In addition to being connected to Goldman Sachs’s heritage, the name felt accessible and added a human element to financial services,” Cohn said. “It created this one-on-one conversation from a person, i.e., Marcus, to another person.” One of Goldman Sachs’s founders was Marcus Goldman.

In practice, the bank followed the advice of Lippincott’s Hancock. Using a human name inspired the startup to have actual people handle customer service calls, with no automated-operator pinball preceding contact. “Having a human pick up the phone immediately is another example of us humanizing financial services.”

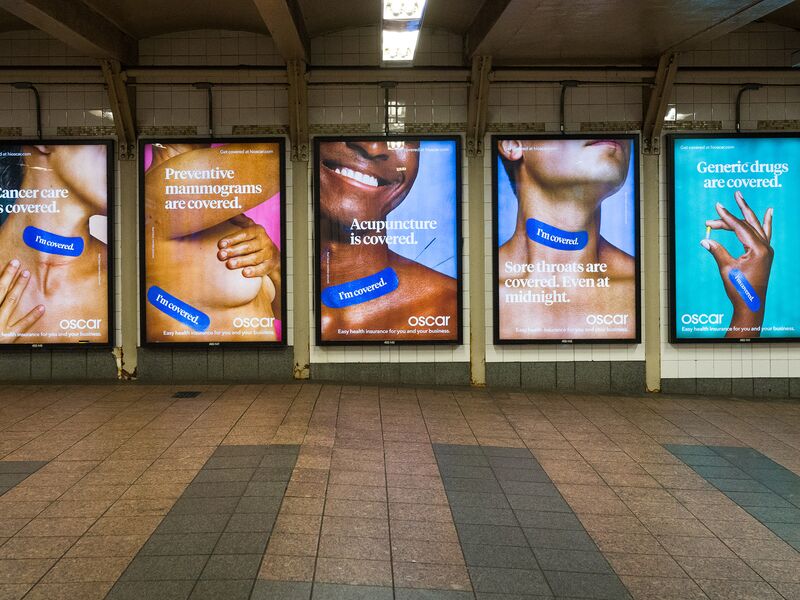

Oscar

Oscar, the health insurance startup co-founded by Jared Kushner’s younger brother, Josh, was based on the idea that the health-care system is so daunting that an effort to humanize it might reap dividends.

“Oscar engages and empowers its member to navigate a complex, costly health-care system,” said Mario Schlosser, co-founder and chief executive officer. The key to this effort was to create a more human approach to health insurance, which meant, in part, finding a brand name that would reflect it. “We chose the name ‘Oscar’ because it’s simple and human-focused,” explained Schlosser.

Many of the company’s advertising efforts used a conversational tone, taking advantage of the friendly sounding name (though some Oscars were famously a bit grouchy) with phrases such as “Hi, we’re Oscar,” “Hi Oscar” and “Meet Oscar,” said Emma Riccardi, the company’s spokeswoman. As with Marcus, there’s also a personal connection tied to the brand: Oscar was the name of Kushner’s great grandfather.

“Having the ‘Oscar’ name continue to be this friendly, personable human name, that point is still core, and—I say—the string that has connected us from when we first launched in 2012 to today to the future of Oscar.”

Casper

Like many startup stories, the tale of mattress company Casper begins inside a New York apartment.

“We had a roommate whose name was ‘Kasper’ with a “K,’” explained Parikh. “He didn’t quite fit on the mattress that he had in his room, so we started thinking about the name ‘Kasper.’” Eventually it stuck—only with a C, because the other way didn’t make sense, he said.

At first glance, their reason for pairing a human name to a mattress company seemed counterintuitive. “We specifically didn’t want something that would just connect us to mattresses,” Parikh said. “Mattresses happen to be the first product we would sell, but we always knew that it had to be about something more than that—about living a better life, especially as it correlates to rest and sleep.”

For a product as intimate as a mattress, the need to create something that “feels very human” was important, Parikh said, and the name was key. “We realized that having something that makes it feel like it could be a person actually kind of lets your guard down a little bit and lets you have that deeper connection,” he said.

Cora

In 2016, Molly Hayward founded subscription-based organic tampon company Cora. While searching for a name, she knew it had to be something feminine—but not “girly.”

“A lot of newer brands in the space were using euphemistic names, and that completely gave me the ick,” Hayward recalled. “When I said ‘Cora’ for the first time, I thought it was nice. It’s short, easily a woman’s name, but not that common.” The company, created on the idea that menstruation shouldn’t be commercially stigmatized, also chose Cora because it was meant to bring to mind “core,” evoking a subtle feminine sensibility.

“When you think of where many of these industries have come from, it was very dehumanized,” Hayward said. “It was euphemistic in some senses, it was abstract in many ways, and there was this lost connection between the person and the brand.”

Warby Parker

Yes, it’s two names, but the story behind them shows that meaning nothing at all can also offer an advantage.

When Dave Gilboa left his pair of $700 prescription eyeglasses on an airplane, he decided not to bother getting them back. This was a bold decision for the future co-founder of Warby Parker, since he had just arrived in Philadelphia to start his MBA at Wharton.

Bonding over his frustration, he and three classmates decided to start a company aimed at personalizing the eyeglass-buying experience while drastically reducing prices. “The best brands build a strong emotional connection with consumers, and we wanted a name that would give the sense,” Gilboa said. “We joke that finding a name that we all liked was the hardest part about starting a company—took us about six months.”

The team went through about 2,000 potential names until Gilboa stumbled upon two Jack Kerouac characters. They decided to combine them—Warby Pepper and Zagg Parker—into “one that sounded somewhat familiar but not like anyone” their customers would know.

“Given that most people don’t know someone named Warby, people don’t come in with preconceived notions about the personality of our brand,” said Gilboa, who is also CEO. “It was this interesting, unusual, sophisticated canvas that we could craft our own brand into, and that’s what we were looking for.”

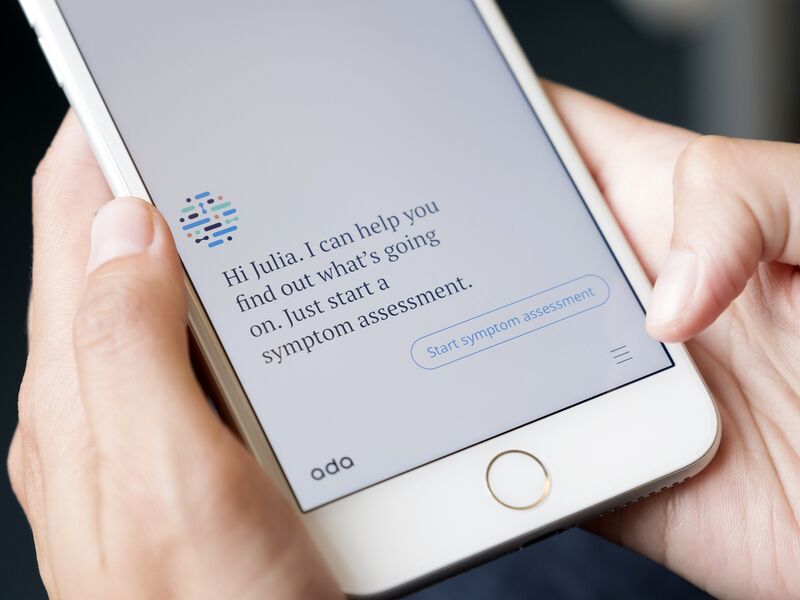

Ada

Launched in Berlin in 2016, Ada is an interactive chat service that combines artificial intelligence and medical knowledge to provide explanations for common symptoms. Like many AI-based companies, the human name plays a key function in the interaction between digital assistant and user. (Think Siri or Alexa.)

“Friendly conversation, underpinned by medical precision, is at the core of everything Ada does,” said Daniel Nathrath, a co-founder and the company’s CEO. “Interactions with Ada should feel like you’re speaking with a friendly, assured and trustworthy medical expert.”

Nathrath said the name “Ada” was a nod to the street name of its headquarters in Berlin, which is Adalbertstraße 20. “Ada, pronounced similarly to ‘aider,’ which means helper, is what our ‘guide’ is,” he said. The name was also that of Ada Lovelace, an early computer programmer who recognized the full potential of a “computing machine,” which Nathrath saw as a nod to his focus on AI.

“Ada is always there when you need it, and takes the time to listen. With a professional and respectful manner, Ada aims to help you better understand and take care of your health.”

Read more: www.bloomberg.com

![[Video] How to get rid of bed bugs in Toronto](https://www.thehowtozone.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/maxresdefault-2-100x70.jpg)